Monterey Train Depot Museum

/The gift shop at the Monterey Depot Museum has graciously agreed to stock Replacing Ann and I want to thank Julie Bohannon for that. When I visited the museum recently to deliver the books I took the opportunity to snap some pictures and make some notes to share with you.

When the Tennessee Central Railroad finally topped the plateau in 1890, they quickly realized that the climb up the mountain would tax their steam engines and by 1905 a maintenance facility was built in Monterey and the station there became the headquarters for the Eastern Branch of the Tennessee Central.

This was a real boon in the local economy. Of course the railroad brought in jobs but it also opened up markets for coal, lumber and agricultural produce that previously could not reach markets.

General John T. Wilder was instrumental in getting the railroad up the mountain because of the coal operation he planned in Wilder and Davidson. He is often mentioned in the museum and in fact, there is a large plaque outside with good information about him. One of the two houses he built in Monterey still stands watch over the depot and the Imperial Hotel which he built to serve railroad employees and passengers is still next door.

Most of the original buildings are gone, as are so many landmarks of Monterey’s heyday. There were two operating passenger depots in town - the original depot from the early 1900’s burned as did so many wood-framed historic buildings in Monterey. The rebuilt depot stood long after the close of operations and was eventually dismantled. The roundhouse burned in 1949 and was never rebuilt. However, the old coal chute can still be seen adjacent to the remaining tracks. Some tools from the shop were recovered and they are now displayed in the museum.

There were numerous tracks in place when the railroad was moving passengers as well as freight across the Cumberland Plateau as well as maintaining engines in Monterey. The museum boasts a beautiful diorama of the town and the orientation of the tracks to the depot can be seen clearly on it.

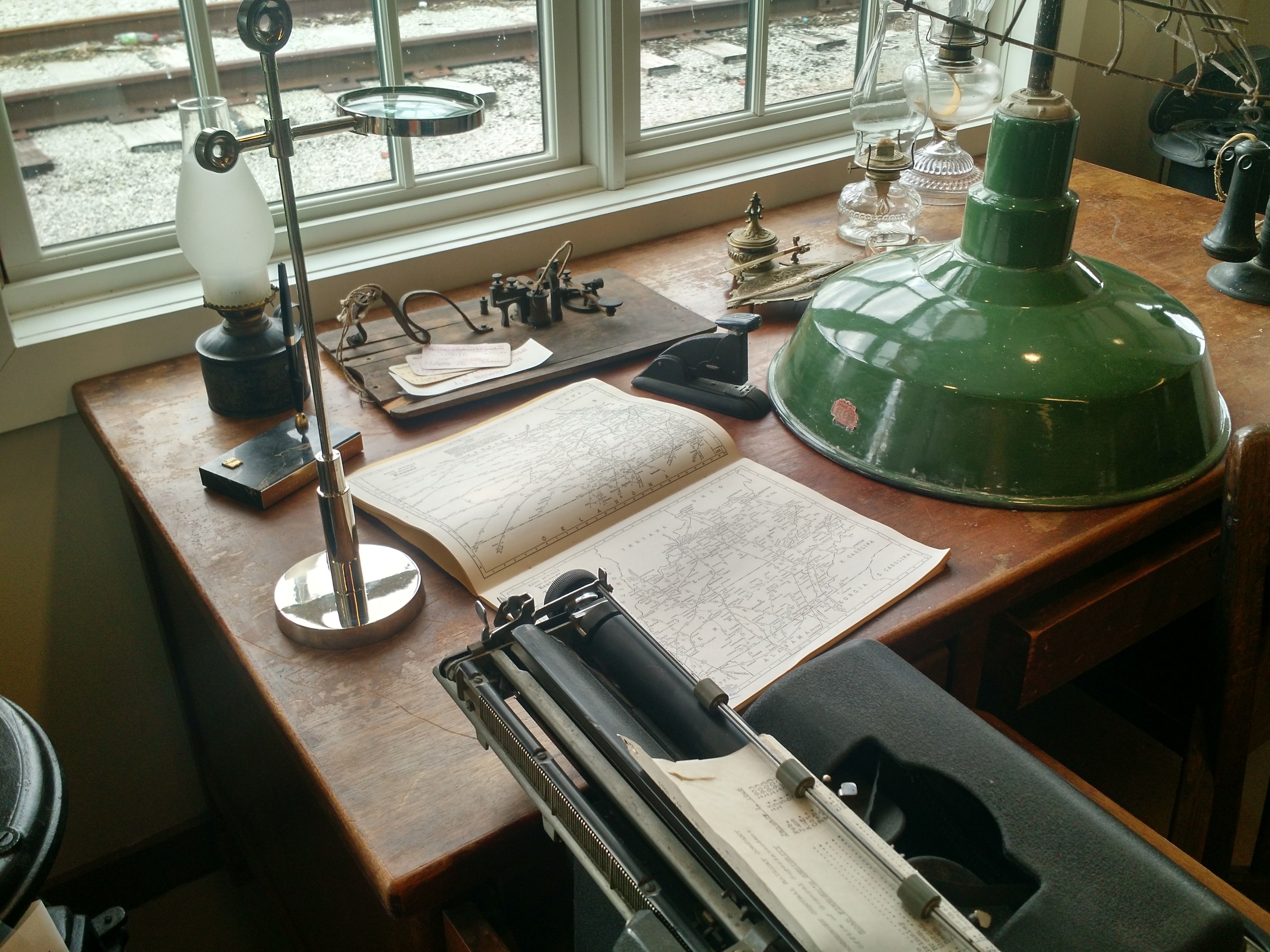

I particularly enjoyed the beautiful display of a stationmaster’s desk, complete with telegraph. There are a number of maps and graphs that anyone interested in railroad or Plateau history would enjoy. This one in particular is a whole history lesson in itself with information on the mining companies that operated, where stores, schools and post offices were located and even who owned some of the farms and homes in the area. Manual Powell, a Wilder miner, created this map.

The scope of the Monterey Depot Museum encompasses the whole community, not just railroading. The Monterey Hospital is represented as well as a wonderful tribute to the city’s contribution to our military. Community exhibits are routinely featured. When I visited, Confederate History Month was beginning and volunteer Linda Whittaker was assembling an exhibit in that honor.

Admission to the museum is free and it is open Monday through Saturday 10:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. If you’ve visited before, please leave a comment below and tell me about your experience there.