Soap Makin’ per Callie Melton

/The following is from an article written by Callie Melton for the Standing Stone Dispatch in the early 1980’s. I present it verbatim.

Soap making was a full day’s work and it just didn’t start on any day you up and thought about making it. You had to look ahead and figure out the next time the moon would full… then you set the day, for if you made the soap on the waning of the moon it would all dry up to nothing. All winter the meat scraps had been carefully saved in a big oak box in the smokehouse. It is true that we used all of the pig but the squeal… soap making proved that.

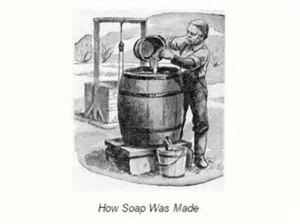

The night before you were going to make soap, bucket after bucket of water had to be carried from the rain barrel and poured in the ash hopper to leach out the lye. Then, the next morning right after breakfast, the big was kettle was set up and filled with water also from the rain barrel… you had to have soft water to make good soap and leech out lye.

A fire was put under the kettle, and while the water was getting hot, the women were busy getting the meat scraps ready. When the water was boiling, the lye was put in. You kept adding the lye until you could swish a feather from a chicken’s wing through the water two or three times, and then when you pulled it through your fingers it would slip… slipping meant that all the feather part would slip off from the shaft. Now that the lye water was strong enough, you began putting the meat scraps in.

You put in a handful at a time, stirring all the time with the soap stick…the soap stick was a stout stick made from a limb of a sassafras bush. The sap from the Sassafras made your soap smell good. When you stirred, you always stirred clock-wise, for if you didn’t stir your soap right it wouldn’t set… and a woman was judged not only by the way her young’uns acted, but also by the kind of soap she made. You added the meat scraps a handful at a time until the lye would not eat up anymore. Then you stirred your soap carefully and cooked it slowly until it began to get thick. Now the fire had to be raked out from under the kettle, and the soap let cool. When the soap was cod, you covered the kettle with wide boards to keep out the dew or rain until morning. The next morning you cut the soap out in blocks, and put it on wide planks in the smokehouse to cure. Good soap was hard and creamy smooth when it was cured, with not bits or pieces of uneaten meat, and it lathered up good when you washed with it… Soap you took a bath with was made from butter or lard and was whiter and finer and you always stirred it with a fresh sassafras stick.