Mountain Speech – per James Watt Raine

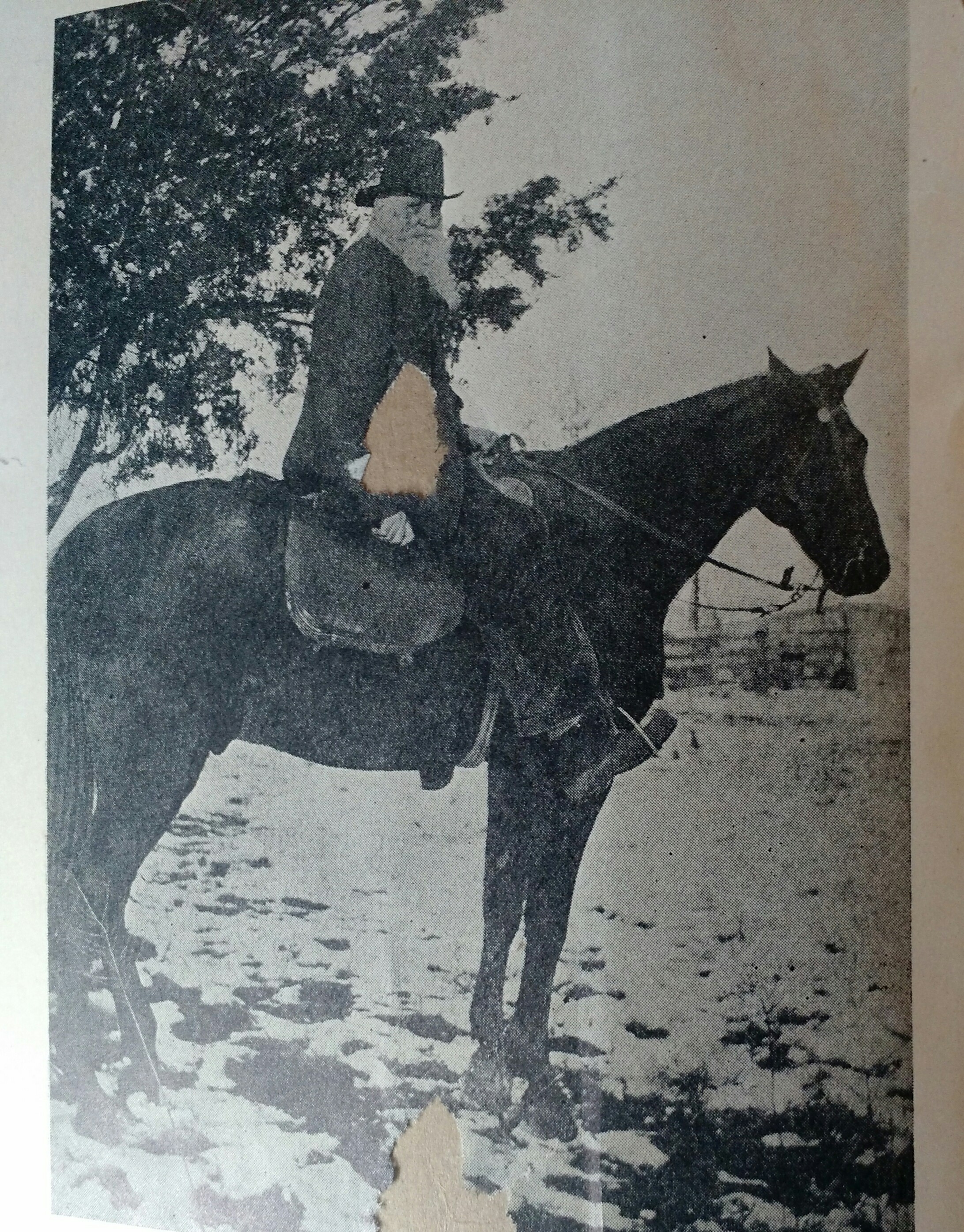

/James Watt Raine as pictured in The Land of Saddle-bags.

The brown spots are simple worn off the page of this very old book.

A handful of you told me you would be interested in Mr. Raine’s thoughts on Mountain Speech and Song and I’m happy to oblige. So we’ll star this article with a confession – I sure got my comeuppance preparing to write this.

I thought I had a working command of proper English even though I often choose the more comfortable, mountain vernacular. Could be, I was mistaken for I found words here that I still use every day – and in fact have been writing in manuscripts – believing they are good English. (Hmm, that explains why Microsoft Word keeps flagging Church-house every time I write it; who knew that “church” referred to the building in written English? I suppose I thought it was the people who are the church and if I referred to the building where they meet then I needed to clarify.)

As I read Mr. Raine’s chapter on mountain speech, I was thrilled to learn that many of the mountain words we routinely use are not just plain wrong, nor are they ignorant inventions. Instead, they are the language of the great poets and playwrights - of Shakespeare and Chaucer, Milton and Spenser and of course of the King James Bible.

He tries to address the why of mountain language and if you remember this book was published in 1924, his logic is sound. Due to the remoteness of our land, many years passed with little traffic from the outside world that would bring slang words to infiltrate the original language of the Victorian settlers. There have always been a few books among us and those certainly affect the reader’s vocabulary and some young’uns have gone out to school and brought back finer speech. Any citizen of the 1920’s would be stunned by the changes we’ve seen in technology, but even then language was having to adapt to the industrial revolution and its inventions.

I’ve often heard how someone “clum the ladder to the loft” and it turns out Mr. Chaucer wrote the past tense of climb similarly when he used clomb and Edmund Spenser (author of The Faerie Queen) used Clomben. I’ve probably recently said I “drug a stick out of the yard” and we always say if you hurt your ankle you’d better “wrop it up in brown paper and vinegar” – although that’s the only time we use wrop I think.

Raine gives credit for modern usage in adding “ed” to past tense words such as throwed, growed and knowed – and would you even think twice if someone told you she “throwed out the garbage”? In a similar fashion we add “es” to form plurals of both nouns and verbs since milk really “costes a lot these days,” and the Christmas lights “twistes all up when you unpack them.”

I wish I could remember which of my elementary school teachers took issue with my pronunciation of “it” preceded by an h. I remember being seated, lectured and made to “sound out the word and write what you’re saying.” To that well-meaning teacher, I’d like to point out, “Hit were good enough for Chaucer”.

Some of the terms Mr. Raine points out as vividly “word-making” or “phrase-making” are so much a part of the English I hear all the time that I’m struggling a little to find the fault of them.

“The moon fulls tonight.”

“Grannie’s been bedfast for a long time.”

“Children grow up directly.” (He doesn’t point out that we pronounce that “dreckly”.)

“I want to buy a pretty for my child.”

Now there are a couple of his custom-made examples that I would have used differently and I wonder if that’s a difference in Cumberland Plateau and West Virginia dialects. While we don’t think of buckets or churns being wooden anymore, most of us would quickly understand the meaning of “the butter churh fell to staves”. However, my use of the adjverb “common” would tend to be slightly negative – as though the person being described was not of very high character. However, Mr. Raine defines it as “…affable, mingles with folks as an equal”.

He does include a number of phrases and terms that I am completely unfamiliar with such as:

Iron and delft – iron pots and pans and dishes

destructious – meaning clear enough as causing destruction

disfurnish – he doesn’t translates but offers this sentence: “If it don’t disfurnish ye none, I’ll pay ye later.”

half-side deep – again, no translation but it’s the measurement of a river.

wasted – used or spent but not squandered.

I continue to be amazed by our language and the longevity of these Victorian, or even way back to Elizabethan, terms. I can’t tell you what validation it offers to hear this champion of the mountain people relating our language back to authors and poets whose work is still highly revered.

He shares one statement from an eight year old girl when asked, “Was your new baby a boy?” she replied, “Yes, hit was a boy – and hit’s a boy yit.”

Next week we'll see what Mr. James Watt Raine had to say about Mountain Music!

**UPDATE 12/19/15

A question was posted on Facebook about our use of "fixin' to" and I am so fascinated by the results of a little research on that phrase that I wanted to share it with everyone.

According to "Words Gone Wild", the phrase "has a distinguished etymological history, dating at least to the 14th century, when fix meant “to set one’s eye or mind on something,”" and probably stemmed from the Latin fixus which means “immovable, settled, or established.”

Had I not read this, I would have guessed that the phrase came from preparing something. For example, no one would criticize someone “preparing a meal for my family” but some would sneer at my “I’m fixin’ some supper” – but they have the very same meaning. Well, it seems people have been fixin’ to do stuff for centuries. In 1716 The Oxford English Dictionary cited fixing as preparing and in 1871 Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote “He was fixin’ out for the voyage” to indicate preparations.

And for those that would say this is totally Appalachian or Southern, “In 1907 the Springfield (Massachusetts) Weekly Republic proclaimed, “What a pretty night! The moon is fixing to shine.”