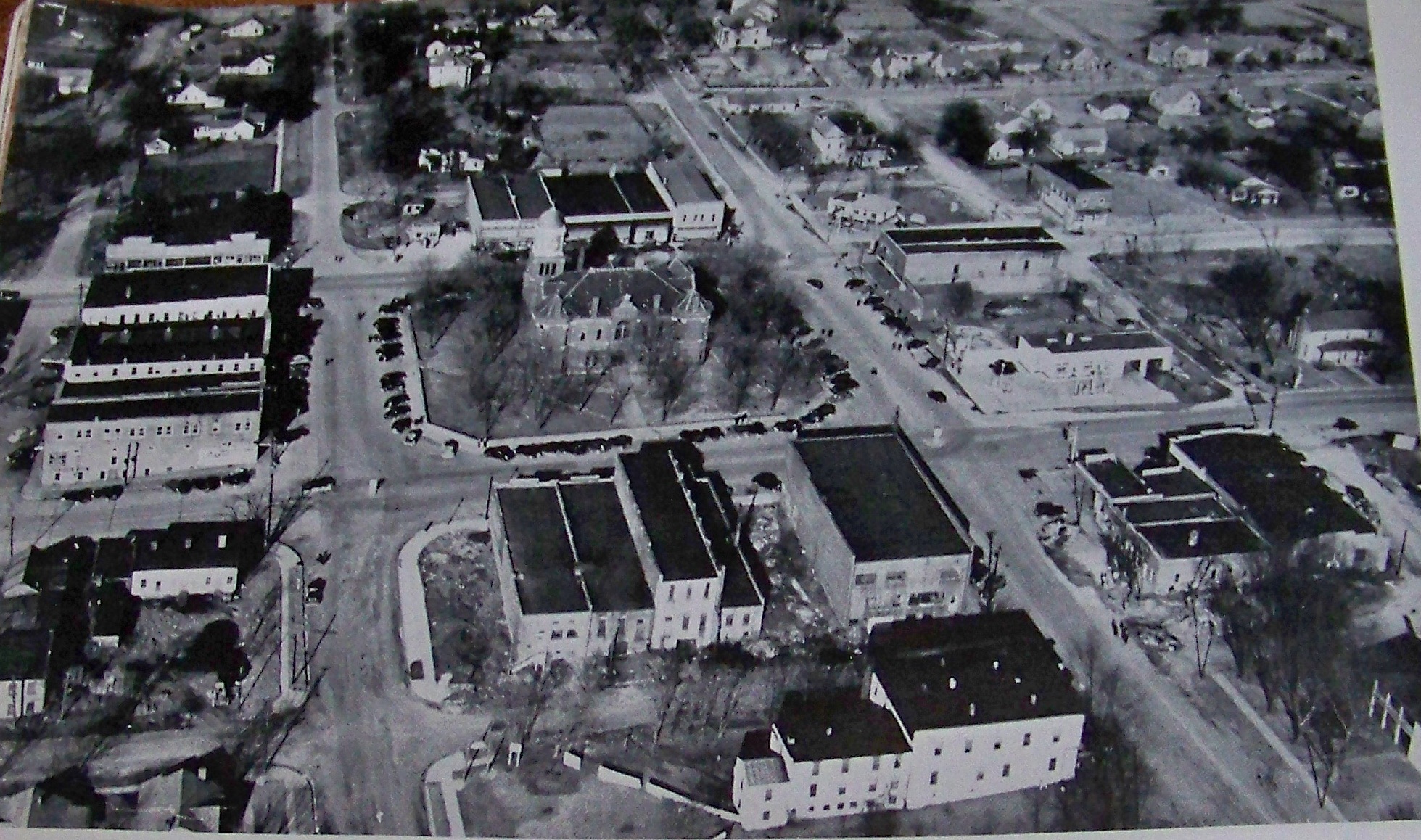

Cookeville, Tennessee “Thrift and Vision”

/This week’s stop in our 1940’s Tour of the Upper Cumberlands is Cookeville, Tennessee. The March of Progress publication dedicates a whopping eighteen pages to the town and I am fascinated by the information it shares as well as what seems omitted.

I never tend to think of myself as an historian. Yet, I am quite eager to preserve the history of the plateau region and I suppose that qualifies for the title. Recently, I’ve been troubled by a trend in America to revise our history. As we study the past, there are things that we applaud and things that we mourn – but they are both history.

I confess that in reviewing the “March of Progress” story about Monterey last week, I purposely omitted a racial observation by the publication’s author. Undoubtedly in 1940 many towns were quick to promote their “abundant supply of native, white, efficient labor.” However, in the context of this blog and our focus on commemorating Appalachian history, I felt that element was out of place. When I began working on the Cookeville story and found that amid details about the brand new City Hall and a National Guard Amory which cost $60,000, the African American population was noted as residing “just outside the corporate limits”.

Now, here on the plateau, we have never been at the center of civil rights movements or thankfully the unrest some of our nation has seen of late. While I know that prejudice exists on the mountain, I never saw first-hand any unkindness based on race or religion and I am awfully thankful for my own ignorance in this area. Perhaps some of you readers who may have a better grasp on 1940’s history in America can comment and help us understand why the author would have even mentioned this separate community. We’ve seen that a lot of the articles in this booklet are geared toward recruiting business and industry, but there is no indication given here that the residents of “Bush Town” are offered for any particular type of labor. Surely they would have been a part of the larger labor pool for new businesses locating in Cookeville. He does note that the races are “economically indispensable to each other” but doesn’t elaborate any further.

Ironically, the author seems to see no inequality in his statement for in the next paragraph he notes the phenomenal growth of Cookeville “due to a spirit of courage and cooperation”. Then the following section opens with, “Out of the chaos, penury and prejudice which characterized the years following the tragedy of the Civil War…” I suppose it is possible that he held no particular bias and is simply reporting the factof where “resides the colored population” and that they do have “their own schools, churches and community life”. This is one of the challenges of reading a historical document with modern eyes.

In 1940, Cookeville was the proud home of Tennessee Polytechnical Institute, and there is a beautiful two page spread dedicated to the school. Surprisingly, after the detailed account of Baxter Seminary, the information here is simply a nine point summary with a list of departments within the school.

Ellen Dee Webb, First woman to solo a plane in Putnam County. Note that she appears to be wearing a parachute.

Separately, the article notes that the institute has contracted with the federal government to train pilots with the head of the mathematics department serving as coordinator to the Tennessee Flying Service. At the time of publication, twelve students have already received private certificates and another class has started with an unknown enrollment. They have trained one woman, and she is pictured with the caption “The heroine of the air.” Miss Ellen Dee Webb of Richard City, Tennessee was the first woman to solo an airplane in Putnam County.

Sometimes in reading an old periodical, the advertisements can teach as much as the text. The Cookeville article seems to have a lot more ads than the other towns we’ve visited. On in particular was fascinating to me; Hotel Shanks is pictured and its location is noted as West Main Street, opposite the depot. I don’t believe that building is standing today, at least not if the Cookeville Depot Museum is located where the train depot was in 1940.

One of the Terry Brothers who owned a dry goods store on the square

Finally, I’m going to include two horse pictures. It seems there were some fans of the Tennessee Walking Horse at work on this booklet for we’ve seen similar pictures before. The president and vice president of The First National Bank were of the Wilhite family, and Miss Sara Elizabeth WIlhite is pictured driving a fine example of the breed.