Trains and Riding the Rails

/Trains are a favorite subject of mine – there is a romance about the idea of rail travel that draws boys and girls of all ages. The day of the railroad was a slower, sweeter time – at least in my imagination! Imagine then my joy when the Monterey Depot Museum invited me to speak at an upcoming fund raiser. I have all kinds of ideas bumping around in my busy brain as I try to organize this presentation. More importantly, I am immersing myself in rail-research. So I thought I’d share some with you.

I found a great little book entitled Railroading in Putnam County by Cookeville Depot Museum (2003) from which this article originates.

Cookeville, TN looking down Broad Street prior to the arrival of the Tennessee Central

For years, local residents knew that the Upper Cumberland held a wealth of natural resources. However, without roads or mechanized means of traveling on them, and with no railroad any cash crop had to make it to a major waterway. From Monterey, Celina was thirty-five hard miles and the closest steamship dock. That must have been utterly impossible for farmers of the mid-nineteenth century. Therefore, most folks just raised what they needed and survived on what they raised.

Then in 1893 the first trains began to make the long climb up the mountain to Monterey and almost magically opened the world’s markets to lumber and coal as well as livestock. The idea of an east-west railroad had been alive for more than half a century. In 1866 an engineer first surveyed the region for the Tennessee and Pacific Railroad. He saw the wealth of resources the region had to offer. He also saw the steep grade and rough terrain that would have to be conquered.

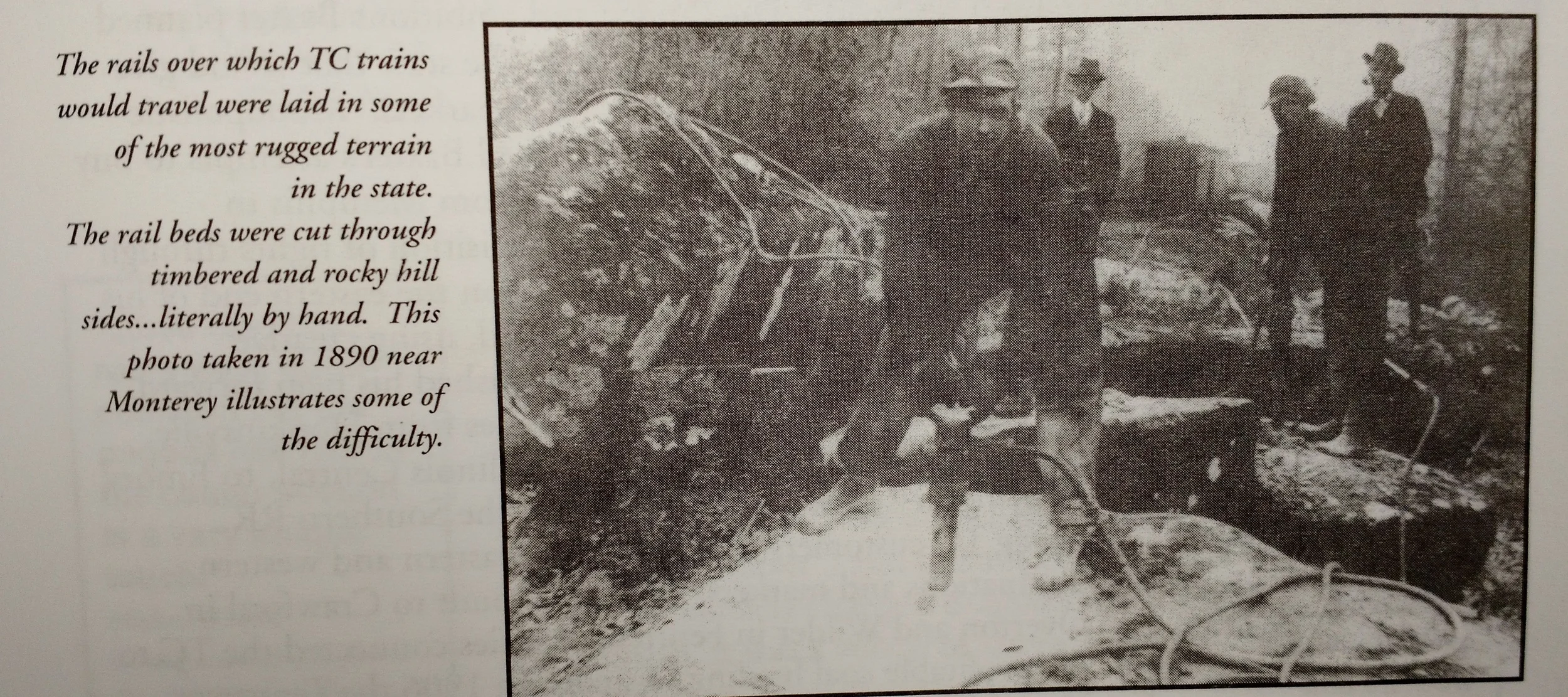

Those obstacles were overcome by sheer force of many hands. Timber was cleared and rocks blasted to lay the tracks first from Nashville to Cookeville, then on to Algood and Monterey.

Key to the rail project finally moving forward was the purchase of mineral rights to thousands of acres of Fentress, Overton and Putnam counties where coal beds would be harvested for the nation’s persistent energy needs. Thousands upon thousands of loaded coal cars would leave the tri-county area over the next seventy-five years. In fact, it was originally the Crawford family who both bought the mineral rights and funded the laying of the first tracks. Jerre Baxter didn’t purchase the Nashville and Knoxville Railroad until 1893.

However, Mr. Baxter is the one we remember as the force behind what would become the Tennessee Central Railroad. He envisioned a railline from Memphis across the state. He was blocked by other railroads that didn’t want the competition and they were powerful. They kept him out of Nashville proper, forcing him to bypass the city. He turned his attention to the eastern side of the rail but was never able to reach beyond Rockwood.

Still, to the people of Monterey, the TC was a blessing. Directly employed by the railroad, were numerous locals who cleaned and repaired locomotives, laid and maintained track and worked daily loading both frieght and passengers. The whole world must have seemed open to locals who could now ride “the Shopper” to Nashville for the day and be home by nine to sleep in their own beds. By the early 1900’s there were six passenger trains passing through Putnam County each day. You could ride the long distance to Nashville, or you could hop off at any of the communities along the way.

Prices seem low to us today, one resident told of riding from Monterey to Ozone in the late 1930’s for thirty-five cents. Of course, he was earning ten cents per day at the miscellaneous work a school boy could pick up. Still, that thirty-five mile jaunt would have been impossible without the railroad.

The Tennessee Central called itself “The Road of Personal Service” and every member took that motto to heart. From the flagman who would help you step out of the tall car to the brakeman who hopped between the cars to manually apply brakes as the train made the descent from Monterey to Algood, everyone along the route seemed eager to serve their customers. No doubt they were happy to have the railroad and the many, many opportunities it provided them.

These were boon days for the Upper Cumberland region. Jobs were available for local folks and were drawing in slews of outsiders as miners, railroaders, loggers and all of the services those cash-yielding jobs require. The Tennessee Central would continue to haul freight through the region until 1967.