The Preacher and the Old Woman that was a-livin’ in the Dark

/Callie Melton includes in “Pon My Honor” a section she calls ‘One for the Road’ and this story falls into that section.

Up here there’s always a whole passel of jokes and tales going around about preachers. But they are always good-natured jokes and tales, for we are very careful to tell them on our own denomination. This is done for two mighty good reasons. First, we just don’t joke with anybody or about anything that we don’t think a right smart of. Then, too, we all hold mighty strong with what we was brought up with. Why, it’s just like family. You can say anything you want to about your own blood and kin, but you just d-double dare anybody else to open his mouth about anybody that’s a-kin to you, no matter how far off it may be.

So, since I was once a member of that church, and still have mighty strong leanings in that direction, I’ll tell this one on the Campbellites.

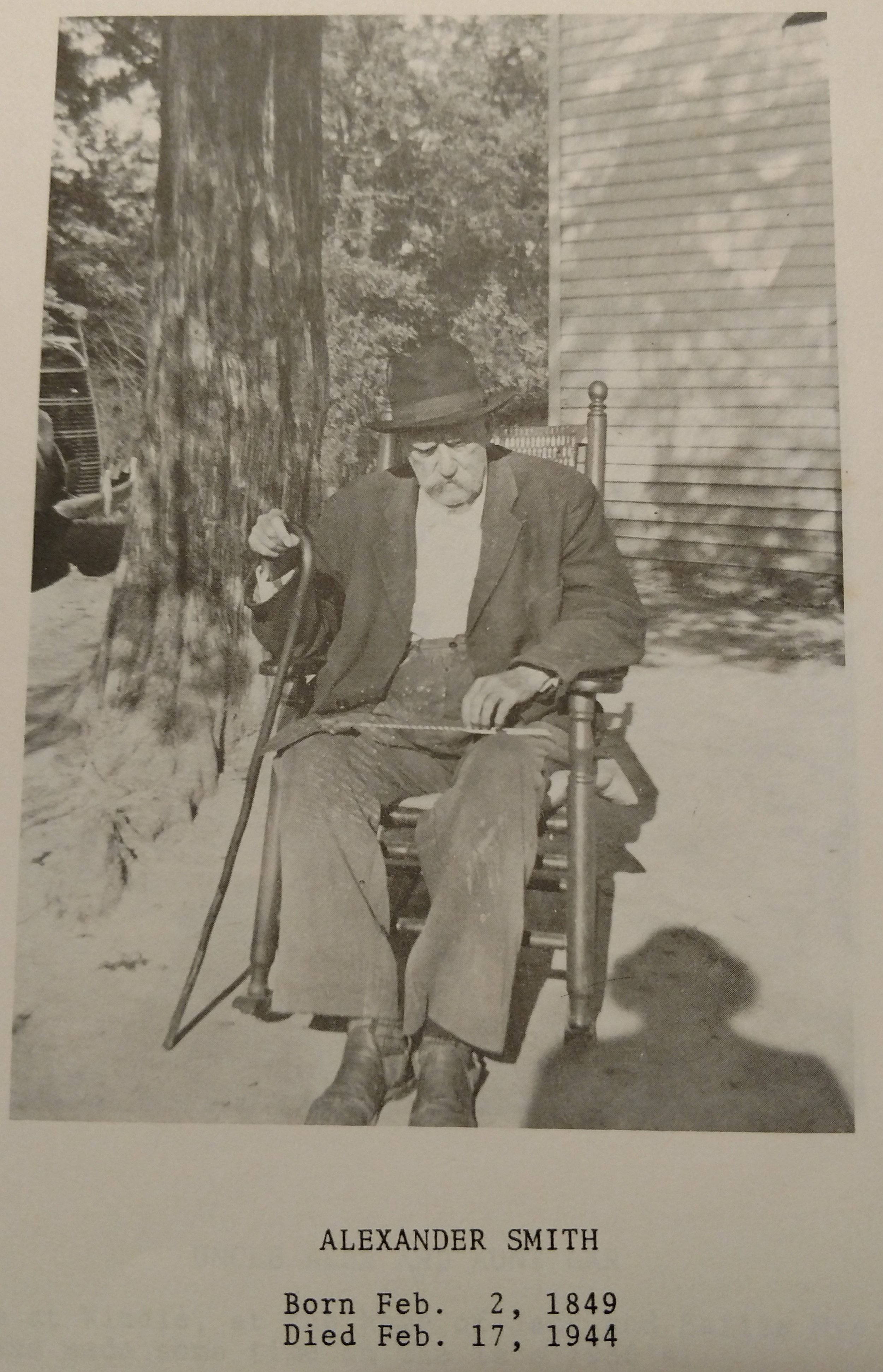

Picture courtesy of Jane Ashburn

One time there was this here Campbellite preacher who went away back up in the mountain to Walker Holler. Now don’t ask me where Walker Holler was, for if I told you, you still wouldn’t know… so let me get on with my story. He was wanting to hold a protracted meetin’ up there if he could find enough people and a good place. From what he’d heard about Walker Holler, them poor people didn’t get much gospel up there.

So, one day he’d just put his Bible and his song book in his saddlebags and had started out. He rode, and he rode, and he rode till finally he’d gone about as far as he could go when he come to this house.

He hollered the house, and this old woman come to the door. He told the old woman that he was a stranger in them parts, and he asked her for a drink of water. She told him to get down and come in. So he got down, hitched up his mule and went in to get his drink and to visit awhile.

Him and the old woman talked about the weather and the crops, and then the Preacher told her that he was trying to find out if there was any Campbellite in them parts.

“Why, I don’t know,” she told him. “My old man hunts a powerful lot, so you kin go out to the smokehouse and look amongst his hides. You jest might find one o’ them varmints.”

The Preacher just set there and looked at her for a minute with his mouth open. He was might nigh dumbfounded at what she’d said.

Then he asked her, “My good woman, don’t you know that you are a-living in the dark?”

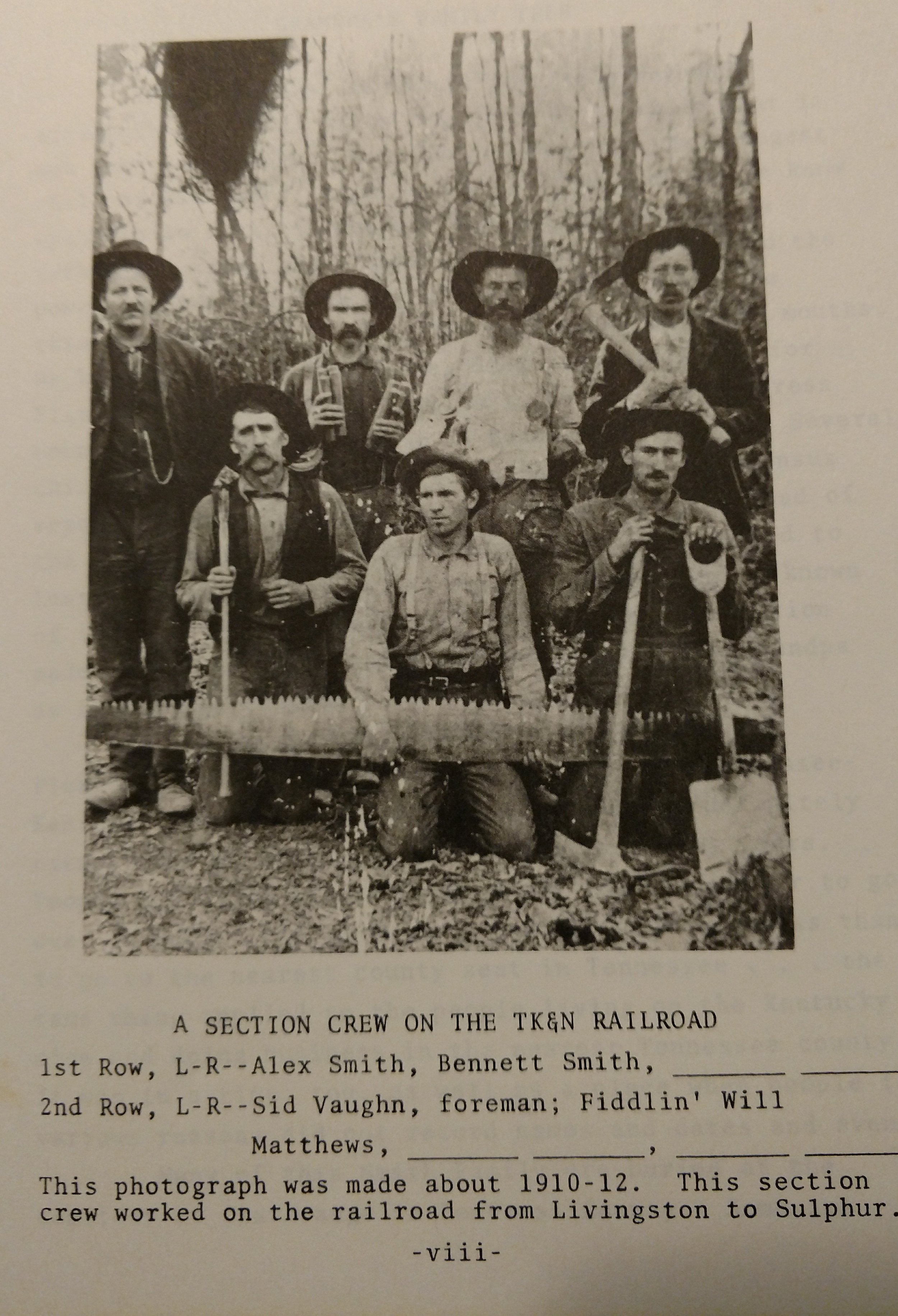

Picture courtesy of Jane Ashburn

“Oh! I shore do,” she said, “and I’ve been a-tryin’ fer quite a spell to git the ol’ man to cut us out a winder. But you know he holds that it’s bad luck to cut out an openin’ atter the house is done built.”

The Preacher was plumb flabbergasted at this, so he just said, “But don’t you know that there’s a Judgement Day a-comin’? Don’t you want to go?”

The old woman fingered her apron for a minute, then she said, “I hadn’t heerd about hit, but I wouldn’t git to go anyhow. Hit’ud be too fur to walk. And you know we don’t have but one ol’ mule and the ol’ man alllers has to ride him.”

Now the old woman just about had the Preacher up a gum stump for something else to say. Finally he asked her, “But don’t you know that Jesus died fer you?”

“Oh! Mercy no!” she said. “Why, I didn’t even know that the pore feller was ailin’.”

At this the Preacher just got up and went out and got on his mule and took off home. When somebody asked him later how he made out up in Walker Holler, he shook his head and went on mumbling to himself, “I wouldn’t a-believed hit iffen I hadn’t a-heard hit with my own years.”