Margaret’s Faith - what's it all about?

/Last week I officially introduced Margaret’s Faith to you. Today I thought I’d share some of the story with you…

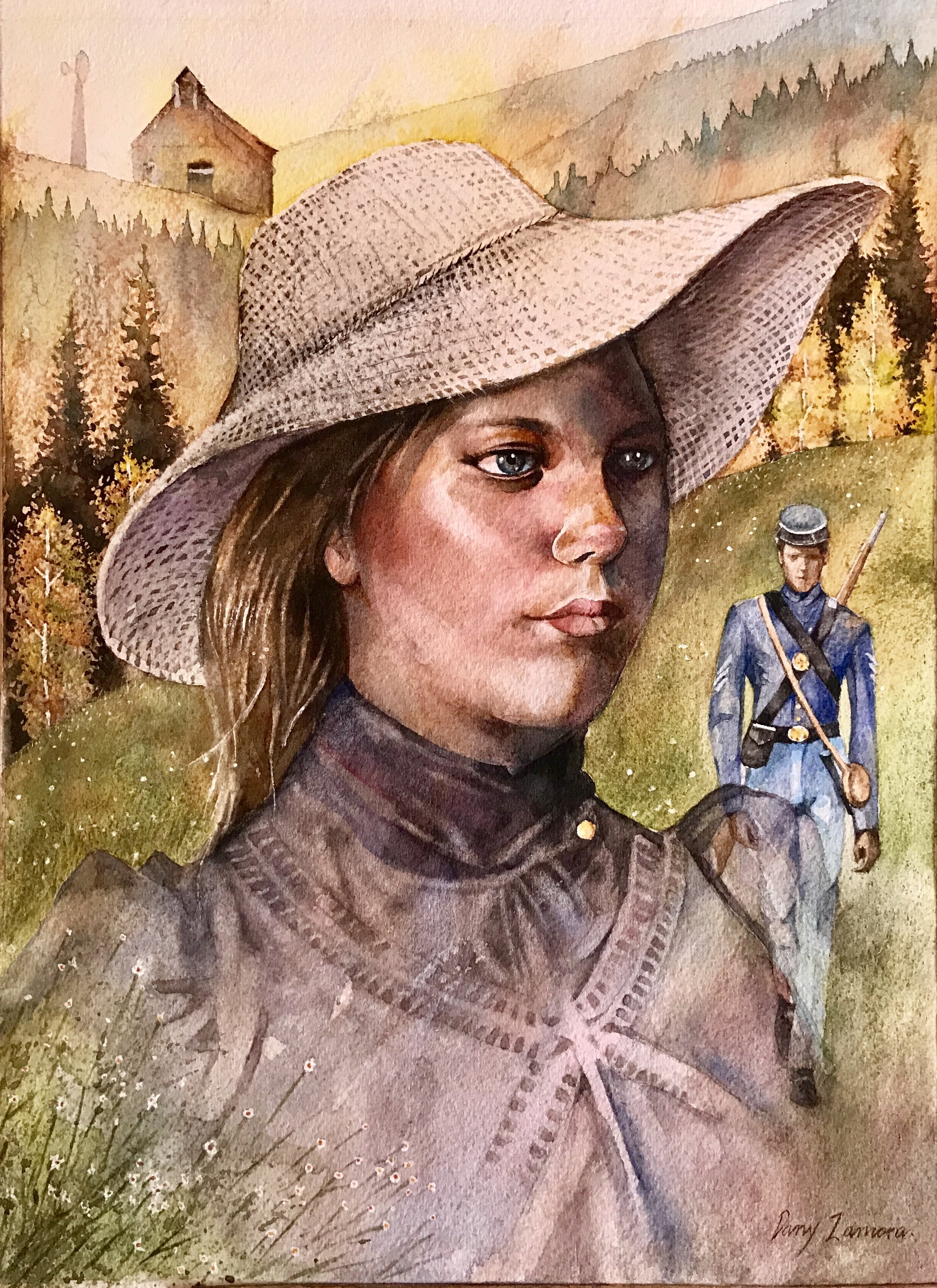

Margaret Elmore reads every printed word she can find. She longs to see the glamorous and adventure-filled world that she’s read about. But in 1863, her father is trying to keep his family out of the way of two warring armies. That means staying close to home on their farm on Tennessee’s Cumberland Plateau.

Then one October morning Union soldier Philip Berai wanders onto the farm. Lawrence Elmore’s first thought is to protect the family and home from a possible raiding party. But this lone soldier turns out to be a danger to only one member of the family, Margaret. He weaves a story of emigrating from Italy with a dream of building a great fortune. Eighteen year old Margaret is mesmerized and when Philip leaves a few days later, she runs after him.

Margaret turns a blind eye to the differences in this man’s values and her family’s. She ignores God’s gentle prodding.

They marry and travel together to Chicago where Philip was living with his brother before the war. When they arrive, Margaret quickly realizes there is little glamour in this city life. But she has been raised to hard work and devotion to family. Without question, she begins to make a home for her new husband.

I hope you will enjoy walking with Margaret from northern Cumberland County, Tennessee to Chicago, Illinois. You will taste the life on a borderland farm – caught between two warring armies as the people of the Plateau were during The Civil War. You may even feel the internal battle Margaret wages when her eyes are finally opened to her situation. Can you identify with her struggle to find joy in the things the world considers desirable? Maybe there’s been a time when you’ve had to face The Lord and admit you rebelled against His will for your life.

You will see a young woman among evil surroundings trying to live a godly life. And you will see her begin to bloom where she is planted.