More about The Cumberland Plateau

/Here are two short articles from Harry Lane’s Tennessee Memorie

Here’s More About the Cumberland Plateau

Mountains on a Plateau? That’s the situation of the Crab Orchard Mountains, which are located on the eastern side of the Cumberland Plateau…at least, that’s the situation if one considers these small peaks to be true mountains, and many would not. Local usage, however, makes these “mountains,” and so the matter shall stand.

This section of the Cumberland Plateau is quite interesting geologically, for it represents the norther end of an up-folded part of the earth’s crust, (an anticline) that, farther south in the Sequatchie Valley area, has cracked off along the fold and moved up and over another portion of the plateau. North of the relatively stable Crab Orchard Mountains is the enormous block of rock that is dislocated along the Pine Mountain Thrust Fault.

This district lies a few miles east of Crossville, Tennessee; the name “Crab Orchard” is well known also, as we have seen, for the building stone that is quarried in this area. The source of the name is a village that is nestled at the base of these mountains.

The highest of these “mountains” lie about 3000 feet above sea level. A few miles farther north, the dissected edge of the plateau itself, called the Cumberland Mountains (however confusingly!), reaches even higher, to 3534 feet at Cross Mountain, the loftiest point between the Smoky Mountains and South Dakota’s Black Hills.

The Mystery of Standing Stone

Remnant of The Standing Stone located in Monterey, TN today.

So completely has white civilization altered the environment of the Cherokee Indians within two hundred years that a place and a monument of considerable significance to Indians of the Cumberland Plateau have almost disappeared from view and from memory – the major damage having been done during the past century. Until the coming of the railway at the turn of the century, there existed on the edge of the plateau at Monterey an Indian monument known as Nee-Yah-Kah-Tah-Kee by the Cherokees and as Standing Stone by white people of the area. The structure was apparently reverenced by the Indians, but the railroad people evidently dynamited the Standing Stone, and only a fragment of the stone (sandstone of the Plateau Caprock) remains today – mounted at the crest of a masonry monument in Monterey in 1895 by the Improved Order of Red Men.

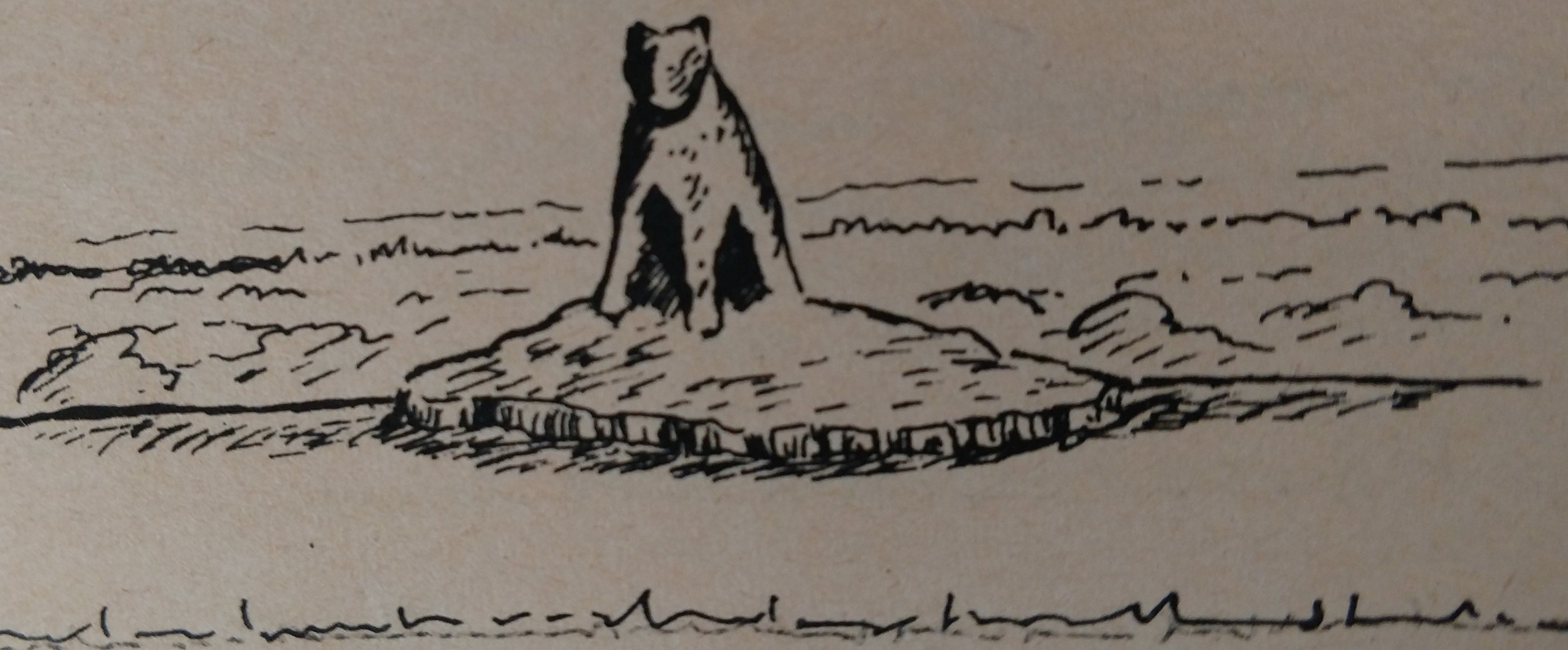

Mr. Lane’s artsitic rendering of the original Standing Stone

Much speculation, but almost no proofs, continues to be cast about as to the real nature of the Standing Stone. Some indications are given that the monument was in the shape of an animal, perhaps a dog, but no one knows for sure. So much for the white citizens’ concern about Indian relics during the last century! It is also uncertain whether the monument was natural or carved. Whether it was a natural formation or something carved by Indians long forgotten (the author prefers the natural formation explanation), it was located in a place that must have had meaning for the early travelers across the Plateau. Apparently, the route past the Standing Stone began as a game trail that was widened by Indian and the European settlers who succeeded them, to become the Old Walton Road of the nineteenth century and eventually a motor road that leads down the escarpment to Buck Mountain, Algood, and Cookeville on the Highland Rim. The effort needed to reach the Standing Stone by a grueling climb from the rim up the western escarpment may have led to the reverential feeling that Indians seem to have exhibited toward the monument. Perhaps this difficult climb seemed rewarded by a view of the unusual formation or carving, whichever it was. It is not unusual for such pilgrimages to be accomplished up steep slopes or flights of stairs to an object or place of worship.

One is reminded at this juncture of Taoist pilgrimages up 6,700 stone steps to the crest of the Tai Shan in China, the Shinto pilgrims’ climb up Mount Fujiyama of Japan, Buddhists’ upslope struggle onto Shri Pada peak in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), the great flights of steps up the sacrificial way of the Mexican pyramids, and the 3,000 stone steps that the Judeo-Christians follow as they make pilgrimages up Mount Sinai. In any case, the Standing Stone, before its destruction, held an imposing position overlooking the Highland Rim a few miles to the west and some 700 feet below the Plateau’s edge.