A Good Place for Green Beans

/

It’s spring and I’m wanting to plant things, loving seeing the green trees and getting ambitious. This often happens to me in the spring and I sometimes bite off more than I can chew.

We’ve been working hard to clean up a field we let get to close to overgrown and now with some dead trees down and scrub brush cut back, I suggested to my husband, “We could do something with this. Why, we could grow a crop of green beans here!”

Of course for a girl raised in the bean field, that’s the first thing that comes to mind, isn’t it? Well, it reminded me of a 4 part blog series I wrote way back in 2013 and I wanted to share that with you this week. Below is the first part and at the end are links to the next 3 sections.

I’d love to hear YOUR Green Bean stories!

The Green Bean Phenomenon

The shadows lengthened as the summer sun lazily began his trek over the horizon. Coal oil lights burned in the homes as supper was finished, prayers were said and children tucked into their beds. Sleep was welcomed, for the people of the plateau had worked hard this day.

Today was not unusual; it was summertime and the green bean harvest was upon us. Early in the morning, men, women and children alike streamed into the bean fields to pull from the vines little emerald sticks of wealth… or at least livelihood.

The green bean phenomenon began its sweep across the plateau in 1933 and lasted until the 1980’s. In the wake of this sensation we find a community transformed, and lots and lots of stories!

As the story goes, in 1933 work was scarce and money short. Well that’s just history – U.S. history. We all know that with the stock market crash of ’29 the nation was plunged into The Great Depression. I’ve heard stories of farm families who had no stake in the stock market, little money in the 20’s and therefore felt the depression years only mildly. Perhaps that would be the case on the plateau as well – for there was no industry here before the depression years, no great companies closed their doors in that time, no breadwinners dismissed from good jobs.

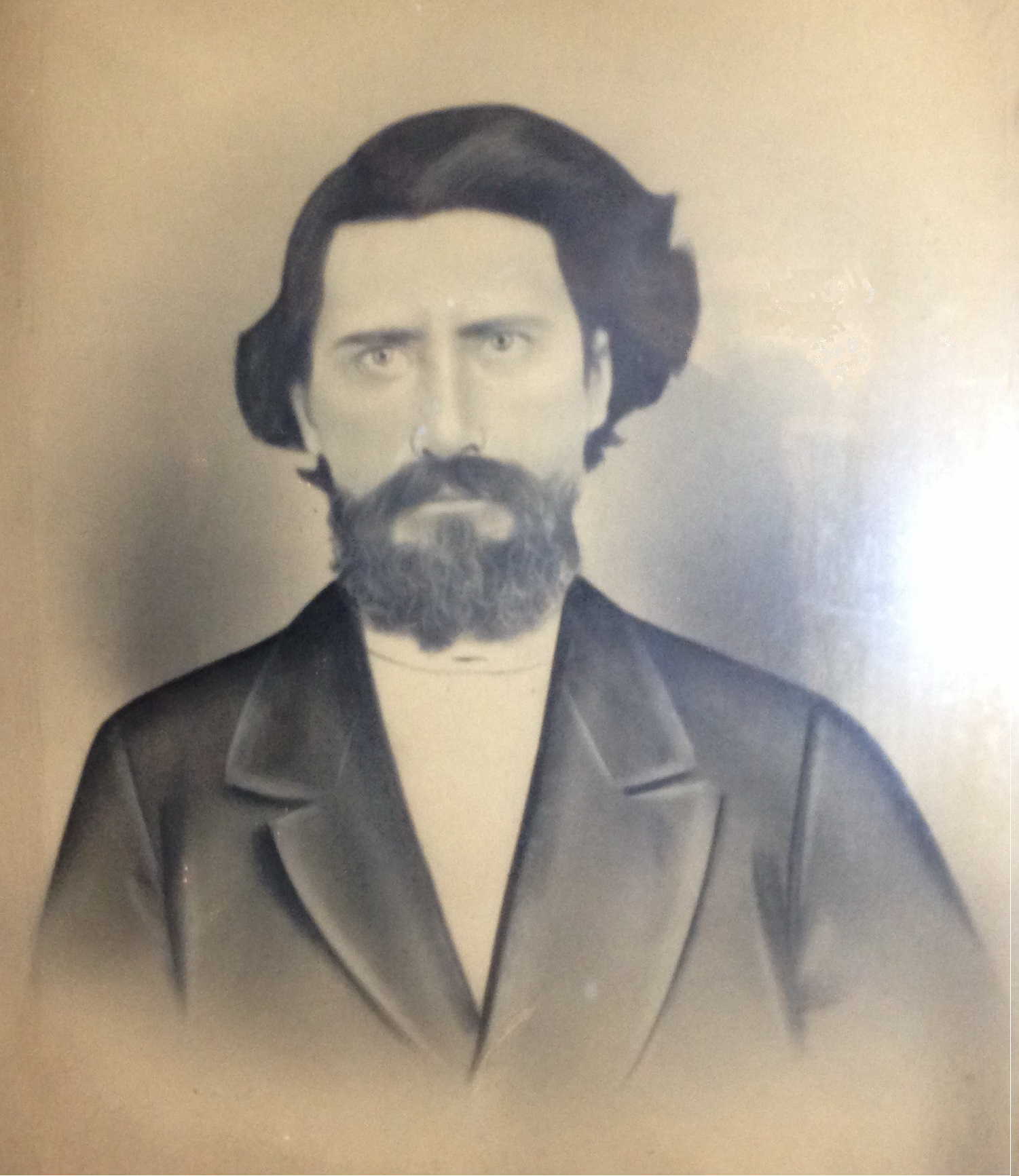

Needing work and unafraid of hard work, Dempse Cooper spotted a truck loaded with green beans headed south through Fentress County and wanted to know what that was all about. He fell in behind him and followed him till he could stop and question the driver.

It seems the load had originated in Kentucky where farmers were growing green beans for public sale. Mr. Cooper saw an opportunity. He planted a single acre of beans. By 1954, 6,000 acres of plateau farmland was planted in green beans and income from the crop had topped 1 million dollars.

Green beans are somehow legendary in our community. So, the telling will take several chapters – or weeks in the blog world. Next week, we’ll visit The Bean Shed! Now you know you won’t want to miss that do you?

Part 3: First Diesel Truck ‘Round Here

Part 4: The Mechanical Pickers