Overalls

/Have I said “Thank you” for reading my blog lately? Certainly whenever I talk personally to any one of you, I’m always thanking you for stopping by my website but please allow me to extend a word of thanks to all of you on this New Year’s Day. I certainly hope we’ll have some good times blogging in 2015!

Tom Norris home from the fields wearing his familiar overalls

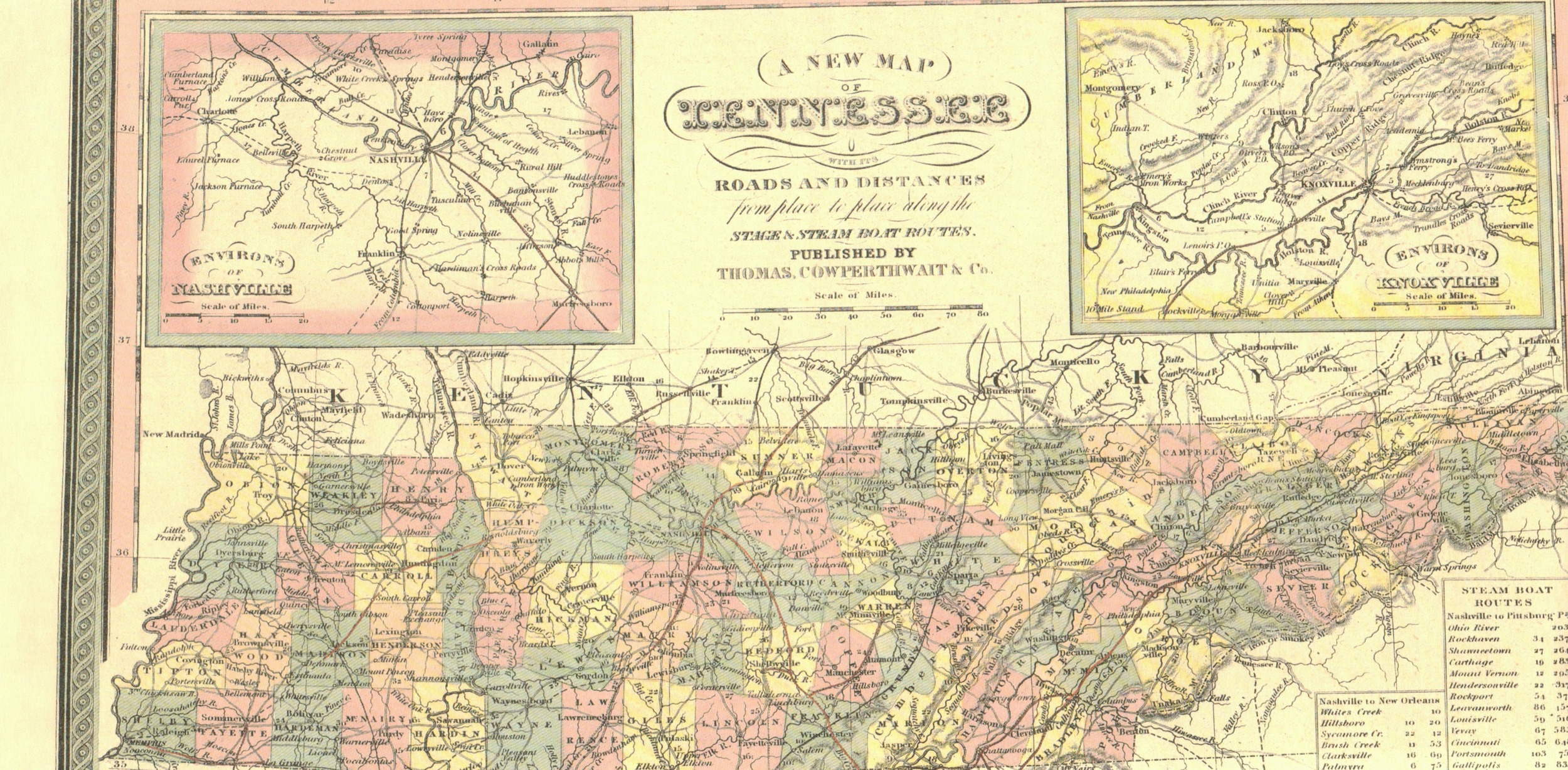

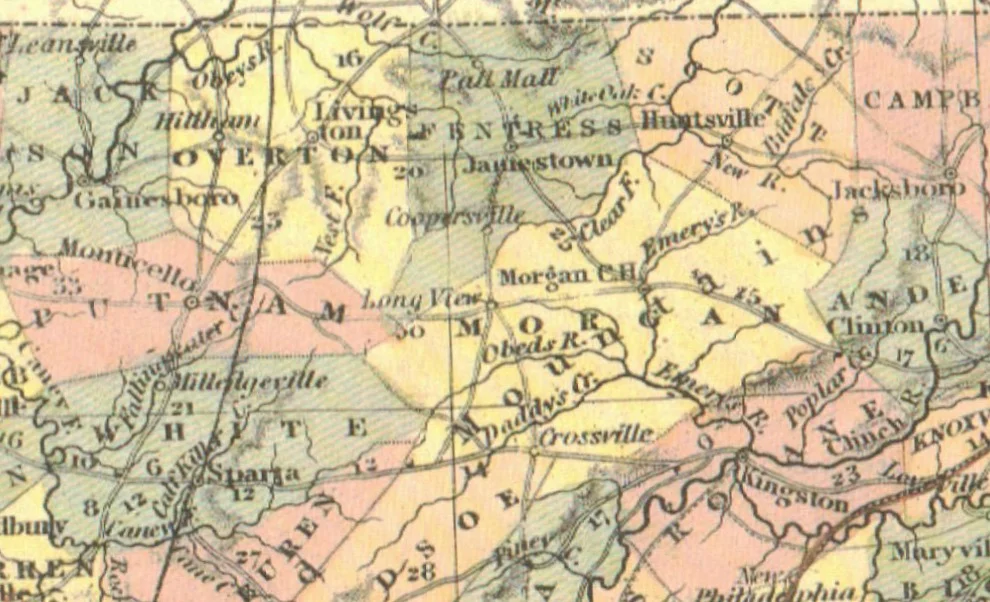

One of the blogs that I enjoy following is AppalachianHistory.net and a couple of weeks ago, Mr. Tabler posted a story about “The Overall Club Movement of 1920.” It was really educational for me (that always makes me feel like my web-time was well spent when I can learn something) because I was unaware of this movement. I encourage you to click here and read his article but essentially these clubs were established to protest the high cost of clothing and their means of protest was vowing to wear overalls (the women would wear gingham) until the prices came down.

When I read about overpriced clothing, I couldn’t help but smile when and wonder what my great-grandparents would say about hundred-dollar-designer-jeans or the prices any of the star-sponsored sports apparel demand. But the bigger thought it evoked was how often did men put on the standard, mountain apparel in the 1920’s and later?

Only known picture of Bob Livesay

Unfortunately, I no longer have anyone to question who was making clothing choices in 1920 but I surely have pictures and stories to refer to. The only surviving picture of my great-grandpa Bob Livesay shows him in overalls. While he had a suit, saved for very special occasions like Decoration Day, he chose the overalls almost all of the time. He even wore his overalls when he went into town. That’s exceptional because all of the stories refer to town-trips as somewhat special due to their rarity and therefore deserving of one’s best clothes.

The Overall Clubs chose their attire because the denim outfit was some of the cheapest available clothing and no doubt their popularity on the mountain reflects the poverty which we are well aware of. While I sense no prejudice in the community toward those wearing overalls, there certainly was a sense that you should do better when you could – such as in going to town or to church events. My grandfather, Berris Stepp, would gladly have worn his overalls all the time but Grandma refused to allow it. She insisted he change when not working on the farm. He worked at Oak Ridge for many years as a welder and while the company supplied coveralls for the workday, he wore twill trousers and sturdy shirts for the trip into the plant; in very cold weather, he would dawn his overalls on top of his other clothes and Grandma fussed every time about him going into work wearing overalls.

Most everyone had a single “good” suit of clothes – but we must remember that even our best outfit eventually becomes worn. I may have mentioned before an oft repeated tale of Coy Key (but as Coy would have said, “I want to hear it again myself” so I’ll share it here). He started walking to town and met Rufus Todd on the road. Rufus had a little better suit of clothes so Coy talked him into swapping; so they found a spot along the creek and changed clothes then continued on their way, Coy on to town and Rufus toward his own destination. That story just seems the embodiment of wearing the best you can – even if it isn’t your own.

Because most families shared a common standard of living, people rarely ridiculed another man’s poverty. However, when a visiting preacher showed up at church wearing overalls the women in the congregation – always more vocal than their menfolk – were astonished. ‘Surely he could do better than that’ they reasoned. And it was the worst disgrace of all if you were laid to rest in overalls.

Today we have a lot more choices and much better means to dress ourselves yet overalls are still around, and maybe they always will be. In fact, it isn’t uncommon to see men or even women out and about in the familiar denim garb. I wonder if those men of our community knew of this move and sure wish I could hear their thoughts about it. Perhaps the next time you buckle a gallus or see an old man hook a finger over his bib, you’ll remember those men who took to wearing overalls in protest in the 1920’s.