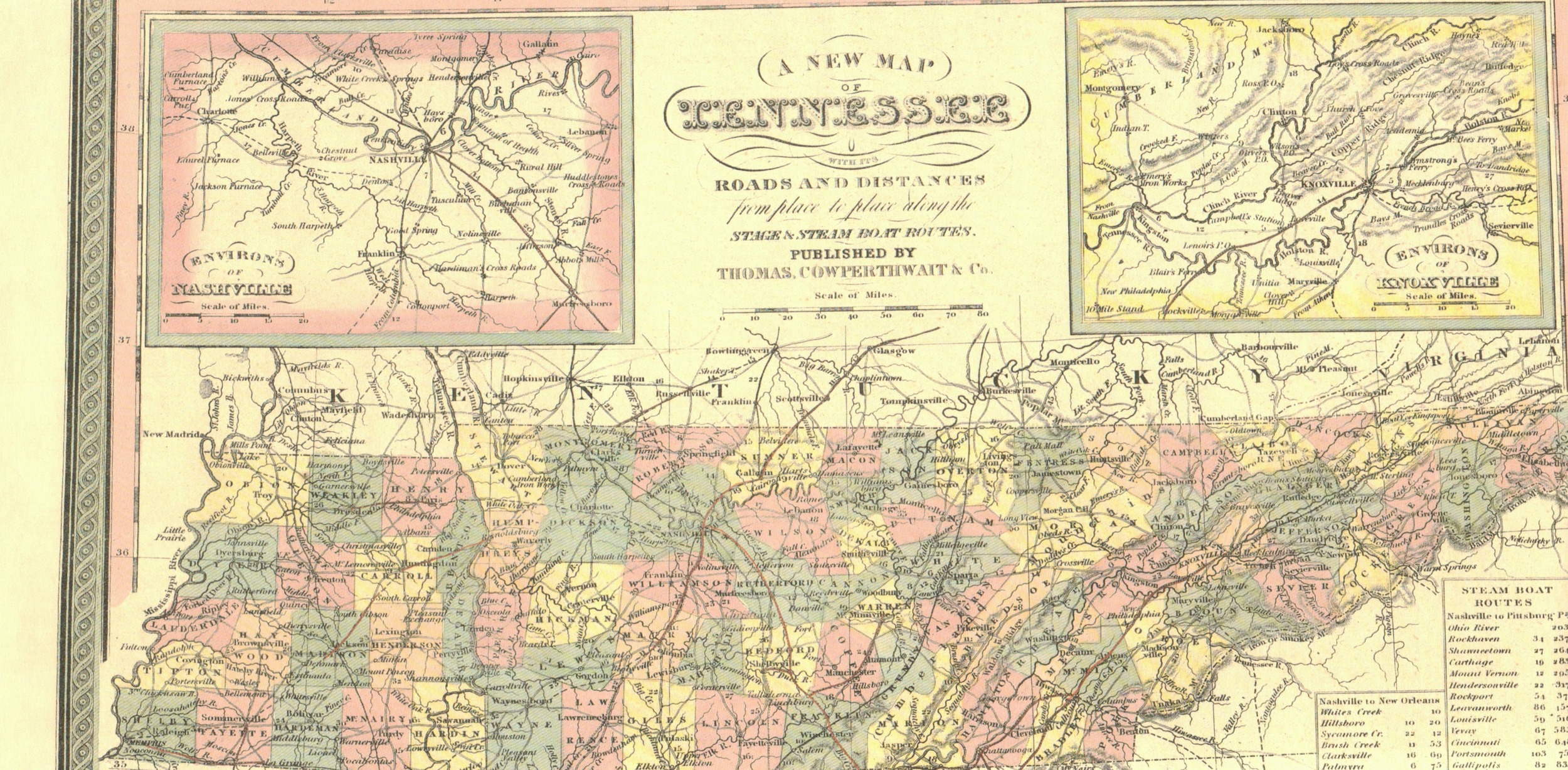

Herman Stepp Heads West

/My family recently lost a beloved cousin, Oliver C. Stepp. While his roots were sunk deep in the mountain, he lived his adult life in Westminster, California and thinking about him made me want to share some of his early experience with you.

When Oliver was twelve years old, he left Tennessee’s Cumberland Plateau with his parents, Herman and Delilah Stepp along with Herman’s sister, Opal and her husband Eugene Welch. They were headed West in hopes the more arid climate would help Herman’s health. Eugene and Opal accompanied them hoping to find work.

Herman had been diagnosed with Tuberculosis and he certainly suffered from breathing problems. However, he did not allow his illness to prevent him working in the Wilder coal mines while living in Martha Washington. Now, I’ve mentioned here before how many men from the Campground, Martha Washington and Clarkrange communities walked to Wilder each day to put in a hard day’s work and we’ve established that while the distance wasn’t insurmountable, the mountain they had to climb certainly seems impossible to us today. Years after Herman’s death, his brother Edsil would remark that he may have been sickly but he didn’t let it stop him from walking across that mountain and working in the mines.

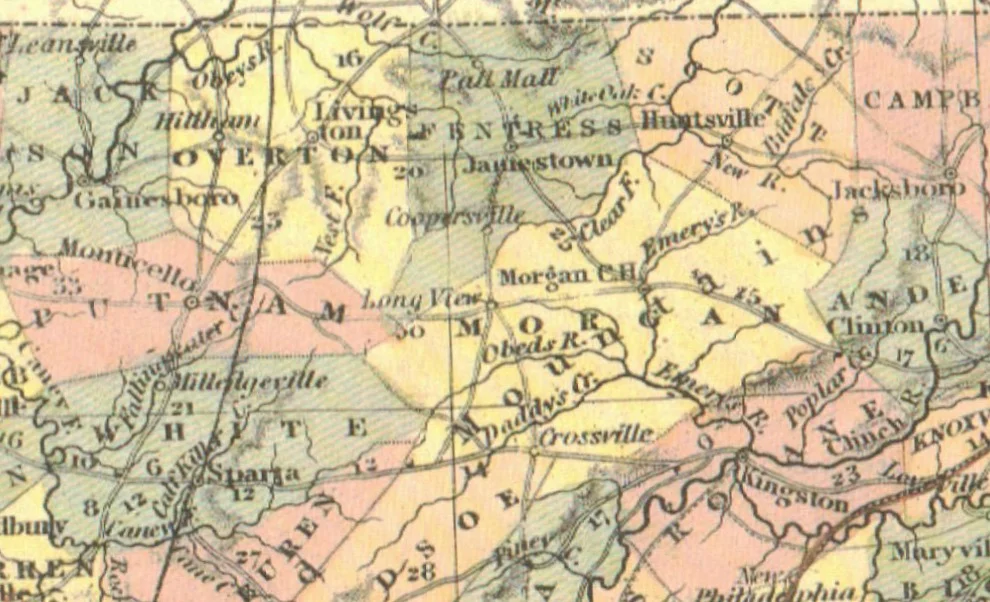

Herman, Delilah and Oliver Stepp

Taken just before they left Tennessee

In fact, Herman was prospering while living in Tennessee. He was one of the first in the community to own a car, as well as a radio. This prosperity reveals just how hard he worked, for the miners were paid by the ton – the more coal a man pulled out of the earth, the higher wage he received.

But prosperity cannot be measured by wage and property and in 1940 tragedy struck the Stepp family and undoubtedly sealed the decision to leave the mountain. Herman and Delilah had two children at that time, Oliver and Anna Rhea. Anna Rhea took sick with a somewhat mysterious ailment that was never really diagnosed. I believe they were able to get her some medical care at Pleasant Hill’s hospital but she eventually passed away at age nine years.

Herman and Delilah are remembered as excellent neighbors and Delilah’s heartbreak touched the entire neighborhood. Studying history is sometimes a rather sterile process – it’s seems easy to recount dates and facts without empathy but my heart breaks anew as I imagine what that little family went through. Death is a part of all our lives and certainly during the early twentieth century, especially in rural America, was almost accustomed to losing infants. However, the loss of a child you have loved and cared for nearly ten years seems almost unbearable. We have always believed the decision to move west was driven solely by Herman’s declining health, yet considering their loss I can’t help but believe that a fresh start in a new environment was a welcome prospect.

So the little band set out seemingly with only the wide West as their destination. The first day they barely made it to Memphis and they quickly lost track of the number of time they had to stop and repair flat tires. Eventually, they made it as far as Oklahoma when Herman declared they would stop for a while. Four years later, Herman’s family resumed their westward journey while his sister Opal and husband decided to return to Tennessee.

The family made it to California, found work and began building their life there. Unfortunately, the arid climate had not improved Herman’s health as they hoped and just four more years passed before he passed away. If you’ve been reading this blog for a while, you know I am continually struck by the difference in medical care today and yesterday and this is another example. While Herman was hospitalized in his last days, he never once had a positive test for Tuberculosis. His wife would always believe he died from Black Lung, contracted from his years in the coal mines where he started working when he was just sixteen.

We began with Oliver’s life with Herman’s passing the young man’s life was forever changed. Prepared to enter college after high school, Oliver instead found himself the head of his family caring for his widowed mother and infant brother. This began a lifetime of service which Oliver rendered with neither bitterness nor complaint. He would be drafted to the Army and serve in Germany while sending his entire check home to care for them. Even after marrying and fathering two children of his own, Oliver continued to selflessly care for friends and neighbors.

I am ashamed that I don’t better know these West Coast cousins and in talking with them there is no hint of our Southern-Appalachian accent but there is a definite sense of family. Whether they realize it or not (and I sure hope they aren’t insulted by the observation), Oliver imbued his daughters with many values he learned on our mountain. As I listened to his oldest daughter talk about her daddy, I kept hearing a description of his grandmother or his aunts and uncles who I have been very blessed to know. I suppose you can take the boy out of Tennessee but you can’t take Tennessee out of the boy.