A Soldier Comes Home

/A Fictional Short Story

Private William Stepp caught his reflection in a dusty window of the Campbell Station Depot and it stopped him in his tracks. Despite the stiff brushing he’d given his blue, woolen blouse and the attempt at shining the heavy leather boots, he looked thin and haggard.

Triumphant, indeed, he thought as he remembered a newspaper he’d glimpsed on the short train ride from Knoxville. The only thing he felt triumphant about was going home. These last few weeks had seemed longer than the entire four years of bloody battle. When the Confederate surrender was announced to his company, he was sure he’d be home in a fortnight but he’d been wrong. The troops had been ordered to Washington, D.C. for a Grand Review. Nothing ever seemed so nonsensical to Private Stepp – and in fact to every soldier around him. Each man reviewed each battle, each campaign, each bitter encounter every-time he dared to close his eyes. William feared he would do this for the rest of his life.

With a shake of his head, he turned his eyes and his thoughts from the morbid and toward the future. He tried to prepare his heart for what he might find at home – he’d seen so much destruction of homes and farms that he dared not hope that the little cabin he'd left behind to shelter his widowed mother and two young sisters would even still stand. But he prayed it would. That had been his prayer every time he saw the burned out hulk of a home, every time he felt the stares from tree-lines of terrified and homeless women and children.

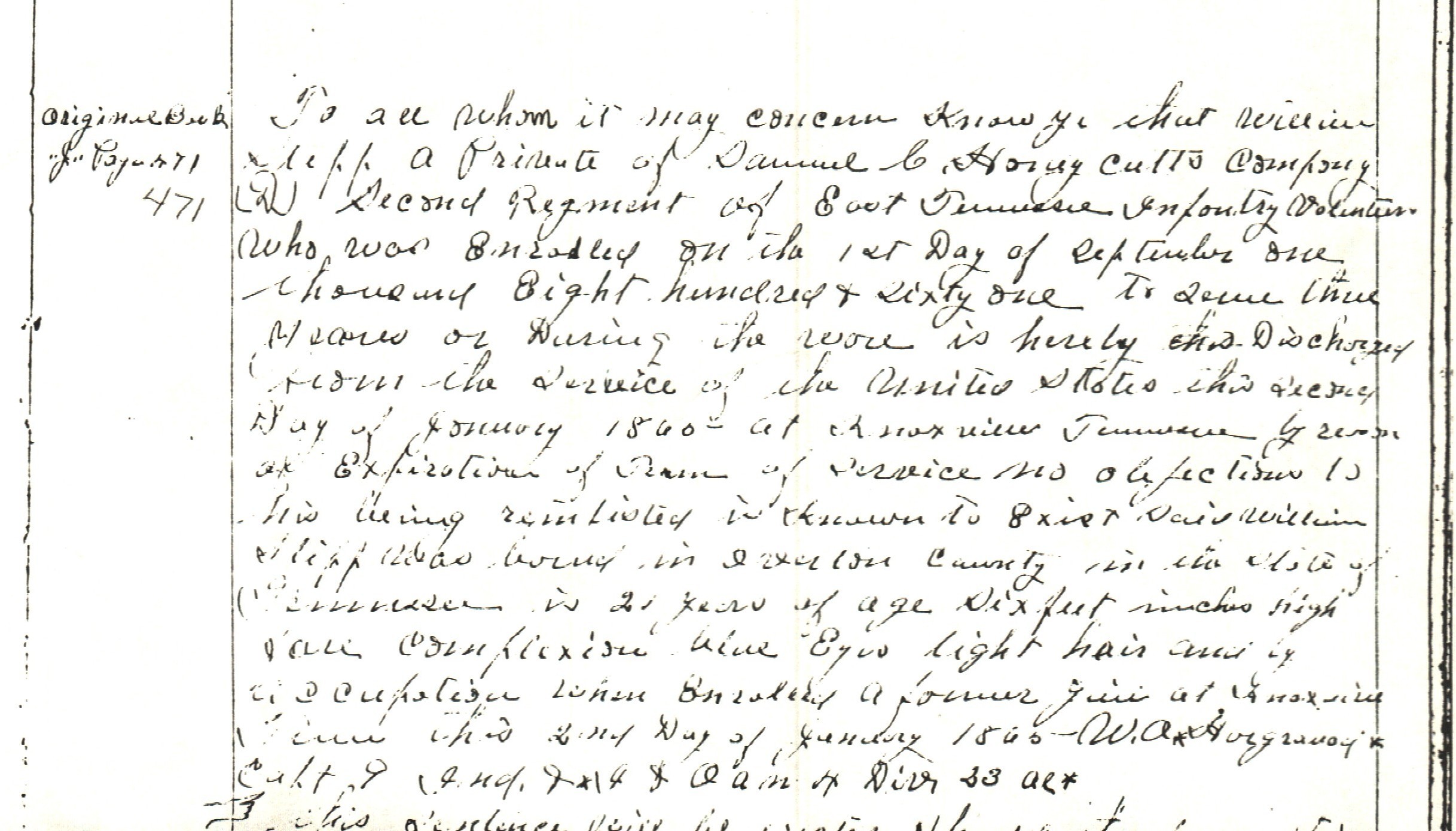

Now Private Stepp was no more. Yesterday, Captain Hargrove had given him a paper in Knoxville that said he was now plain old William Stepp. For the first time in more days than he could count, that lifted the edges of his lips in a half-smile. But this new man, William Stepp, he had a new challenge on his hands. Four years ago, he’d not been off that mountain since his mother carried him in on her lap. Now he’d certainly seen a lot of this country, but he’d been ordered every step of the way, told when to march and when to kneel and shoot; told even when to turn and run in retreat. Since no trains ran to Fentress County, he was given a week’s rations and offered a train ride to wherever he wanted to start his trek. After a look at the ragged map hanging in the captain’s office, he decided to ride as far west as Campbell Station. He knew the mountain well enough to know it wasn’t going to be an easy walk from any direction but at least this starting point got him out of the busyness of Knoxville’s streets. There were so many wagons, buggies and saddle horses that he was sure he’d be trampled at any moment.

Another glimpse at the stranger in the window and he stepped off the wooden porch. Was his pack lighter? Was the rifle in his right hand now an extension of his arm? He turned away from the sun, enjoying the warmth on his back, and took his first real steps toward home.

The climb began almost immediately. There were other men heading generally the same direction and from time to time he’d walk a way with one of them – some in the familiar blue uniform, others in tattered rags of gray. There was no malice in these woods now, they all had the same mission – getting home. He learned the stories of some of the men. One old man said he’d been home twice – deserted in order to make a crop for his family, then picked up his weapon and returned to fight for his land. This one looked exhausted, but not ashamed. He’d fought for what he believed in and William could not argue with that – right now he felt like he would never argue again.

Homesteads were sparse here, and towns even rarer. William slept at night wrapped in the blanket he carried over his shoulder and warmed by a small cooking fire. He ate the hardtack and crackers he’d been issued and enjoyed a cup of weak coffee in the mornings. It had been three days since he’d seen another soul when the leveling land told him he had made it home. Well, it was still miles to the cabin and to his mother, but he knew he was on the mountain now. Soon he began to recognize paths he and his brothers James and Pres had followed as young boys out on a ‘long hunt’. It was a game they’d played, imagining they were frontiersmen exploring the new country. They packed a sack with whatever food Mother could spare and headed out. It mattered little that they had only one gun between them, they were all great hunters and they were sure they’d return with enough meat to see the family of ten through the entire winter. Papa had allowed it, probably because they’d worked so very hard through the hot summer and there was little he could reward them with.

William looked around the terrain he was covering. Even here it was relatively flat, good farm land though the soil seemed a little on the thin side. He smiled now – the smiles were coming more readily with each step he took - thinking of Papa’s tells of settling the hillside. His first stop when he and Mother came from Virginia was on the banks of the fertile Wolf River. However, he’d soon learned he couldn’t get along with the flatlanders who lived there and decided he’d rather eke out a living on lesser ground than be surrounded by people so unlike him. So he headed south and twenty hard miles later, among rolling hills and steep gorges, he decided on a north-facing hillside near The Campground. The infrequent visitors to this well-known stopping point were all the company John Stepp thought he needed. Amanda had not offered her opinion but William would later hear her telling her daughters how happy she was when they were born and she knew she’d have some kind of feminine companionship.

William’s musings stopped short as he topped the hill opposite the homestead. There was the rough cabin, stacked stone chimney with a thin wisp of smoke curling from the top. Emotion washed over him. The war-toughened soldier dropped to one knee, the rifle rattled on the rocks at his side and tears streamed down his cheeks. Here was the victory. Suddenly, for the first time since the surrender was announced, Private William Stepp, U.S. felt triumph.